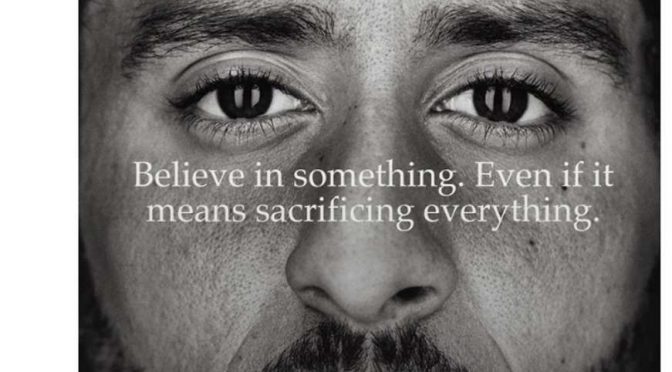

Much of social media has been transfixed this week by Nike’s “brave” decision to sign Colin Kaepernick for its latest ad campaign. Kaepernick had reached fame – and simultaneously destroyed his career in American football – by kneeling during the national anthem at games in protest at anti-black discrimination and violence in America.

Kaepernick’s action aroused a level of annoyance for “disrespecting the anthem”, being anti-patriotic, or simply bringing politics into sport. Of course some of this backlash was driven by racism, but not all of it. Unlike other similar protests – like the iconic black power salute given by Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympics – Kaepernick’s protest was repeated at game after game.

The first thing that became apparent was that Nike had played their move to perfection. They had, no doubt, researched the idea impeccably before putting it into action. The game-plan rolled out roughly like this:

- Nike announce they signed Kaepernick.

- An unknown number of angry people (though probably not many) burned their Nike shoes, filmed it, and published their videos to social media.

- Donald Trump tweeted about it.

- Liberals mocked the protests online, made memes, and generally enjoyed themselves while massively amplifying the protests out of all proportion to reality.

- The mass media, always worried it’s missing out on something, piled in to amplify the issue further.

- Pundits argued over whether this was a good move for Nike, or not: would it lose or gain sales?

- Sales of Nike products rocketed by a reported 31% almost immediately.

- (Probably) The marketing dude at Nike got promoted.

Nike had smoothly played a game based on what might be referred to as “information arbitrage”. Arbitrage is the act of profiting by exploiting price imbalances across markets – buying something cheap and then immediately selling it at a higher price elsewhere.

Imbalances in information can be valuable. In rural Africa, before the introduction of mobile phones, a farmer might have sold his corn cheaply to a merchant, unaware that the merchant could sell it for double the price only a few kilometres away. So, the introduction of mobile telephony in Africa was greatly beneficial to subsistence farmer, and cut the profits of middle-men.

In the case of Nike and Kaepernick, the information imbalance relates to American racism. Social media, combined with the dominance of “liberal” thought, has spread the idea that black people in America are subject to terrible, ongoing racism in their daily lives. This idea originates in the very real racism that was endured by black Americans for most of American history, from the earliest days of the slave trade until the post-Civil Rights era. Information was key to ending the segregation and oppression of black people in the US South: specifically, the arrival of cameras to cover civil rights protests exposed a horror that many Americans had been previously unaware of.

The civil rights movement didn’t end racism in America. It only began the cultural processes that began to diminish racism. Such changes must occur across generations. But certainly, racism did begin declining from the 1960s, and that decline was significant and ongoing. Like all vaguely-defined concepts, racism itself is hard to measure, but it can indirectly measured by asking people whether they would be happy living next door to, marrying or voting for someone of another race. And sure enough, such attitude surveys exist. Such surveys show that racist attitudes have been in steep decline since the social upheavals of the 1960s.

For example, the proportion of white southerners who would vote for a black President has risen from about 70% in the 1970s to over 90% now. It’s worth considering these numbers for a moment, because many or most people today would guess at far lower numbers, given the widespread belief that most Americans – especially American southerners – are deeply racist. Why do we tend to overestimate the levels of racism in America?

Movements don’t just decide to pack up and vanish when their goals are reached. This was especially true of the civil rights movement. Having succeeded, in the 1960s, in shining a light on racism, and winning the passage of civil right legislation, the movement continued to roll forward into the 1970s, 80s and 90s. Ironically, as racist attitudes slowly declined, the perception of racism went in the opposite direction. The less racism there was, the more people believed there was. This was fueled by a new generation of civil rights leaders, such as Al Sharpton, who would jump on any incident, publicise it, racialise it, and monetise it.

By the present decade, this movement (more correctly described as a “grievance industry”) was finding racism everywhere, and the mass media was willingly reporting all this “racism” without question. To make things worse, social media appeared. The public tends not to understand the difference between anecdotes and evidence, and so social media became swamped with anecdotes that further exaggerated the perception of American racism. Every video of a police shooting became “proof” that all black people were at constant risk of being shot by police (although in reality, two white people were being shot by cops for every black person). When social media got bored of police shootings, it moved on to get outraged about increasingly trivial examples, like some student wearing blackface or a klan outfit to a Halloween party.

When even trivial examples of racism became hard to find, completely non-racist things were deemed to be racist. White people wearing dreadlocks, white people wearing hoop earrings, in fact by 2017 pretty-much-fucking-everything had become “racist”. This mania wasn’t just spread by bored students, but became the mantra of once-sane liberal publications like the Guardian and Salon, which hired black columnists (on the condition they wrote about how damn racist everything is all the time).

Quietly, black people who didn’t feel like the victims of continuous, 24/7 racism were being pushed away from the left bit by bit. They are spoiling a perfectly lucrative oppression narrative. Wealthy and successful black people, and especially those that don’t back the oppression narrative of the new left, are a threat to the profits of the grievance industry.

Here was the information imbalance used by Nike: the American (and global) public believed racism to be far higher than it really was. Nike signed Kaepernick knowing that, inevitably, some idiots would burn their shoes and post the videos to social media. The public and the media, who generally don’t realise that anecdotes aren’t evidence of a trend, believed that the videos constituted a widespread racist backlash against Nike. And so in turn, a tiny backlash created a huge counter-backlash: first on social media, and then in shoe stores.

Nike’s strategy couldn’t have worked without the information imbalance. If American society was really as racist as many now believe, the campaign would have risked losing them significant sales, and they wouldn’t have been able to risk the brand damage. If on the other hand, the public was aware of how small the racist backlash was, there wouldn’t have been a counter-backlash.

All this is fine: Nike’s campaign has demonstrated, again, how weak true racism now is in America. Kaepernick gets a good paycheck, and Nike’s shares rise. Everybody happy. Furthermore, this strategy will only work temporarily, while the information balance persists. The more it’s exploited by advertisers, the less effective it will become. Black people will get tired of being presented as victims, and white people will tire of being saviours. One day, a campaign such as this will generate a broad response from black people: “Stop using your anti-racist virtue signalling as a way to sell shoes!”. And then perhaps, we can finally move on into the postracial era that was prematurely announced with Obama’s election in 2008.